Cuprian tourmalines

The Paraíba tourmaline

controversy

It’s

been more than a decade since the transcendent neon blues

of Brazil’s Paraíba tourmaline first came to market. Like

Tanzanite, Paraíba was named for the area in which it was

mined, a location that has proved to be unique in all the

world. Both of these rare gems have become collectable, and

fine gems of size command princely sums. Traces of copper

and manganese in the molecular structure are responsible

for Paraíba’s stunning color.

Now the term “Paraíba” is

being used to describe other copper-containing tourmalines

from Nigeria and Mozambique, and many in the gem world

aren’t happy about it. These new gems range in color from

shades of robin’s-egg blue to blue-green to green and even

violet. They contain the same ingredients as Paraíba

tourmaline, but in different concentrations. They’re simply

not “Paraíba” in either look or origin, but the sellers of

these stones hope the name’s caché will make their stones

more salable.

Paraíba

tourmaline in Platinum by Alex

Sepkus

Recently

the president of the American Gem Trade Association (a gem

dealer who just happens to have a large inventory of

Mozambique and Nigerian tourmaline), announced that

henceforth the AGTA gem lab would certify all

copper-bearing tourmalines as “Paraíba”, regardless of

origin. He claimed that the AGTA Board had made the

decision, but this proved not to be true. In the face of

outraged opposition, he took a sudden leave of absence and

the AGTA board rescinded the previously announced policy.

The jury is still out on this

issue, but the most recent issue of Gems and Gemology, the

quarterly journal of the Gemological Institute of America,

reported that probable origin of Paraíba-like tourmaline

could now be determined through sophisticated gemological

testing (LA-ICP-MS, see article at right). The

international Laboratory Manual Harmonization Committee,

which includes seven major gemological laboratories, has

for now agreed to apply the term “Paraíba” to all blue,

bluish-green to greenish blue, green and violet albeit

tourmaline that contains copper and manganese, regardless

of its origin. But in this country, the FTC forbids using

place names to describe gems unless the seller can provide

documents to support the claim. Stay tuned–and as always,

CAVEAT EMPTOR.

This month’s sources include the article

“Paraíba-type

Copper-bearing Tourmaline from Brazil, Nigeria and

Mozambique"; and AGTA

member bulletins.

--------------------------------------------

LA-ICP-MS: (Laser

ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry): a

new way to determine origin and detect treatments of

gemstones.

LA-ICP-MS

is an analytical technique used to detect the chemical

composition of gems. It reveals both additives from

gemstone treatments and trace elements that can help

determine a gemstone’s probable geographic origin. And

that’s a good thing.

One of the most troublesome

developments in gemstone enhancement in recent years has

been the large-scale beryllium diffusion treatment of

natural sapphire. This treatment can result in color

enhancement including complete color change in some cases.

(“Rainbow sapphires” are produced by this treatment.)

Unlike previous diffusion

treatments, beryllium diffusion penetrates the entire stone

and is impossible to detect without sophisticated testing.

Originally only the yellow-orange-purple-pink part of the

spectrum was thought to be affected, but we now know that

in all probability, nearly all sapphire undergoes this

treatment, including classic blue sapphire.

In LA-ICP-MS testing, a

minute amount of the gem sample is vaporized by a

high-energy laser beam, and the vaporized material is

ionized into a plasma by a high-frequency power generator.

Even trace elements in the parts per billion range can be

identified. The test leaves a tiny spot on the surface of

the sample, and cut gems are generally tested on the bottom

of the stone in an area that can easily be repolished.

LA-ICP-MS allows gemologists

to definitively diagnose beryllium diffusion and other

treatments. It also makes possible the cataloging of the

precise makeup of gems from specific sources, which may

ultimately solve the dilemma of place-name designations.

This month's sources include "Chemical

Fingerprinting by LA-ICP-MS” by Abduriyim,

Kitawaki, Furuya and Schwarz (Gems and Gemology volume

XLII).

--------------------------------------------

Glass filling

of highly included natural ruby to significantly enhance

clarity

Once upon

a time, a by-product of the routine heat treatment of

rubies was the filling of common small surface inclusions

with residual flux from the crucibles used in the

treatment. Now we are seeing cases where highly imperfect

rubies with significant surface fissures have been filled

with lead-containing glass that transforms their appearance

completely.

The material used is often

very low grade pink, red or purplish Madagascar corundum

but glass-filled stones from Tanzania and Myanmar have also

been noted. The effectiveness of the treatment is amazing

in that it transforms opaque and nearly worthless corundum

into material that is transparent enough for use in

jewelry. However, ammonia, bleach, and even concentrated

lemon juice were found to damage the filler by turning it

white at the surface.

Cavities filled with

high-lead glass can be challenging to see under the

microscope, but most samples recently examined by the

Gemological Institute of America contained gas bubbles and

exhibited a blue or orange flash effect at the interface

between the natural material and the filler. Glass is

significantly softer than ruby, and the filled area may

exhibit an inferior polish to that of the natural ruby

host.

This month's sources include The Loupe and GIA World News

Vol. 15 #3

--------------------------------------------

Buyer

Beware Alert

Glass-filled ruby scam in

Madison, Wisconsin

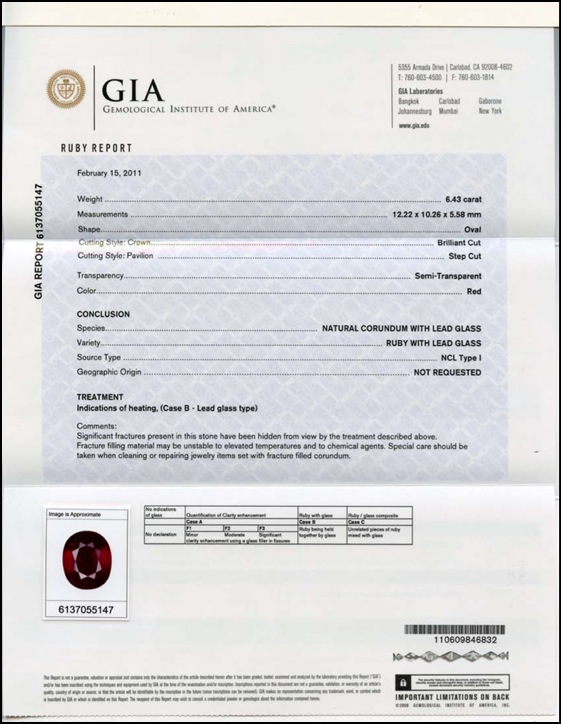

In January a woman came to Studio Jewelers with a 6.43

carat ruby that her husband had given her for an important

anniversary. She wanted it appraised and set in a custom

ring. The ruby was an attractive red color but quite cloudy

in appearance due to numerous small inclusions. The

customer stated her husband had purchased the ruby from a

man he met socially, and had been told it was a natural

ruby. He had paid $1,500 cash for it and was told he should

insure it “for at least $7,500”. She didn’t identify the

seller except to say he traveled a lot, claimed to be in

the jewelry business and dabbled in selling gemstones.

Because the range of possible value in a large ruby is so

great (depending on whether it’s synthetic, natural, heat

treated, color enhanced by beryllium diffusion, or

fracture-filled) Hanna sent the stone to the Gemological

Institute for certification of origin and treatments. The

GIA found the ruby to be extensively glass filled, which put

its retail value at well under $300.

This scammer was able to take advantage of this couple’s

ignorance of the natural ruby market as well as a common

misapprehension about exorbitant margins in the jewelry

business, implying that a markup of 500% or more would be

normal. The undocumented cash purchase leaves the consumer

little recourse.

For more information on

this topic, please read the above article on glass-filled

rubies

--------------------------------------------